- Home

- Coney, Michael

Cat Karina Page 2

Cat Karina Read online

Page 2

But the Estrella del Oeste didn’t even belong to him. It was an ancient Canton car, its days of fast passenger work long over, a broken-down hulk with patched sails and frayed ropes eking out its last years as a track maintenance vehicle. In its time it had held twenty passengers in its cylindrical hull, but now the seats were gone, and the drapes and the luxuries, leaving only a bare cavern some ten meters long filled with the tools of Enri’s trade: wooden pegs, mallets, rope, bone needles and thread, a shovel, a flint spokeshave, and several barrels of stinking tumpfat for greasing the rails and bearings. Enri’s living quarters were there too; a tiny cabin with a bed, a table and a few possessions.

Enri rode on deck, behind the car’s single mast, gripping the mainsheet — the rope which controlled the angle of the sail to the wind — like any crewman on one of the prestigious Company craft, controlling the sailcar’s speed by the tension of the rope and by occasional judicious application of the brake. The wind was light tonight, and he didn’t have to use the brake much.

The Estrella del Oeste lumbered on while the Pegman dreamed of changing the course of history, and a small part of his mind — the professional part — gauged the state of the track by the feel of the deck’s motion through the seat of his pants. Soon the car slowed. He had reached the long climb past Camelback.

The wind chose that moment to slacken.

“Huff! Huff!” He shouted the traditional crewman’s cry and blew pointlessly into the limp sail. The wind dropped altogether.

The car was rolling to a halt.

He stood, a tall, thin figure in the moonlight, and shook the boom, inviting the wind. His mood of elation had evaporated. Now he saw himself as a broken-down True Human in a broken-down car. “God damn everything to hell!” he yelled. It would be morning before he reached Rangua at this rate.

The car stopped. He swung one-handed to the running rail and jammed a chock under the rear wheel to prevent the car rolling back down the grade and losing him what little ground he’d gained. Walking back to a crutch, he swung his mallet to check the security of the fastenings.

The mallet struck the crutch with a solid thunk. In the distance, the moon reflected pale silver on the sea.

“Sabotage!” he suddenly shouted, driving his fist at the sky. “I’m a saboteur and I’m going to remove a couple of pegs from this crutch, so that it will collapse when the dawn car from Torres hits it. Ten important people will die in the splintered wreckage. The southbound track will be damaged too, and the next car from Rangua will pile into the mess. More people will die!”

Obsessed by his vision of destruction he sat down, his imagination racing. The Canton Lord would be on the Torres car. Enri would be waiting near and would pull the Lord free, the instant before Agni struck the wreck into flames. The Lord would give him land and Specialists, whom he would set to building cars. Monkey-Specialists, with deft fingers and tiny minds.

And then.… And then he would search the whole world for Corriente, his love. And he would find her, and she would cling to him, and they would live happily ever —

The wind was blowing.

He walked slowly back to the Estrella del Oeste. There was no hurry, and he was lingering over the dream.

The rail trembled. A dry bearing squeaked like a rat.

Corriente, so warm, so loving.…

The Estrella del Oeste was moving!

It was impossible — yet the dark bulk of the old car was receding from him, wheels rumbling on the running rail, rigging straining to the fresh breeze. He began to run, awkwardly, one-armed and unbalanced on the narrow rail slippery with tumpfat.

“Yaah!” he shouted, like a felino trying to halt a shruglegger.

A burst of clear, feminine laughter answered him. Now he shouted at himself, calling himself a fool. The Tigre grupo had outwitted him again. He could see them now — four girls, leaning on the after-rail, waving. They had sheeted the sail in tight and now, for all he knew, were going to take the Estrella all the way to Rangua South Stage. “Stop!” he yelled.

“Not for a man who dreams of sabotage!” came the cry. “You ought to be ashamed of yourself — and you a pegman, too!”

Damned felinas! He ran on, muttering. Teressa was at the bottom of this. She’d put them up to it, the little bitch. Saba was too timid and Runa would see the consequences, and Karina … Karina was too nice. But Teressa could sway them all. She would grow up to be a bandida, that girl.

Somebody must have touched the brake — Karina probably — because he heard a scraping sound and the sailcar slowed. He reached the door and swung himself inside, blundered through the tools and stink and climbed the short ladder to the deck.

“Hello, Pegman!”

The four girls lay about the deck in attitudes of innocence, and Teressa was even mending a frayed rope. Helplessly he regarded them: cat-girls, descendants of some ancient genetic experiment, come back to haunt Man in the person of him, Enriques de Jai’a, pegman for the Rangua Canton. “I am human!” he suddenly shouted. “I am Mankind!”

“Of course you are, Enri,” said Karina. “So are we.” There was a slight reproach in her tone.

He’d meant no harm; he’d hardly been aware of his own outburst. “You’re goddamned jaguar girls,” he muttered.

“But you love us,” said Teressa, not even looking up from her work.

“Aah, what the hell!” To his intense embarrassment he found tears in his eyes and he turned away, facing north. The wind was strengthening with every moment and he must pull himself together. There was some difficult sailing between here and Rangua; the sailway turned inland for a short distance and cars had been known to jib in the sudden shift of wind. Last year, the Reine de la Plata had had her mast carried away and a crewman killed. Felinos and shrugleggers had towed the disgraced craft into Rangua, laughing derisively.

No, the Camelback Funnel, as it was called, was a difficult stretch for a man with one arm.

“And you couldn’t do without us,” said Runa seriously. “Not in this wind.” She handled the sheets, slackening them off while Saba eased the halliard and Karina, climbing to the lookout post, jerked the sail downwards. Teressa threaded a line through the cringles and in no time the sail was neatly reefed — a manoeuver he was totally unable to carry out himself. The car rode more steadily as the pressure on the lee guiderail eased.

“They shouldn’t expect you to do it all yourself,” said Karina.

“It’s this or no job at all.”

“Then don’t work. Plenty of people in South Stage don’t work. Other people look after them.”

“Listen!” he was suddenly bellowing, placing his hands at the side of his head like mules’ ears. “You’re talking about a felino camp! You people are different! You go around in grupos! True humans aren’t like that. We’re more.… solitary. The weak ones die. It’s good for the species.”

Karina said quietly, “Tonight a True Human helped me.”

“Huh?”

“I broke my leg. I was lying trapped on the rail. She came and mended my leg, and set me free.”

“If you broke your leg you wouldn’t be able to stand on it now.”

“She healed it right away, with a stone.”

“Ah, what the hell.” He wasn’t going to argue.

But her sisters had already descended on Karina and the four girls had become a struggling, fighting mass on the deck; half-play, half-serious. “Broken leg, eh?” Teressa was shouting, twisting viciously at Karina’s ankle. Meanwhile Runa was dragging Karina’s alpaca tunic over her head and Saba, safe now Karina was effectively trussed and blinded, was pounding away at her body with her fists. The Estrella del Oeste rolled on through the night. Enriques de Jai’a turned away, checking the set of the sail. Felinas had no sense of decency, and Karina wore no pants, and how much was a man supposed to take?

“Har! Har! Haaaar!” he roared into the wind, acutely embarrassed by his own emotions.

The struggling mass rolled across the deck

and brought up with a crash against the after rail. He stole a glance and saw that Karina, freed from the tunic and naked, was fighting back. She’d thrown an arm around Teressa’s neck from behind and was throttling her, meanwhile getting a devastating kick into Runa’s stomach. Saba, smaller than her sisters and weaker, left the battle and joined him on the foredeck. She was panting and her colour was not good. Enri put an arm around her.

“Too rough for you, sweetheart?”

“I just get tired so quickly, that’s all. I wish I was like Teressa, I really do.”

It had been a multiple birth, a normal occurence among felinos. More unusually, the babies had all been girls. Although male felino children generally leave the grupos at puberty, either to squire an unrelated grupo or to join the bachelors at the other end of the camp, their presence in the childhood grupo provides a steadying influence in the formative years. The death of the mother had not helped and, with the formidable El Tigre too involved with his revolutionary plotting to guide the four wild daughters of one of his five wives, the girls had gone their own way.

Now Runa was vomiting over the side, Teressa was leaning against the mast, mauve-faced and gagging, and Karina was getting dressed.

“Teressa doesn’t look very happy,” said the Pegman.

Saba looked round, smiled and said, “I’d change places with her even now. She’s strong.”

Karina joined them. The wind had freshened and her hair streamed like flames. “Aren’t you glad we’re here, Pegman? What would you do without us? That last gust would have taken the mast right out of this old tub, if we hadn’t reefed for you.” She made no mention of the fight. It was an everyday occurrence in the grupo, a part of growing up.

But Enri asked, curious, “Why do you always win, Karina?”

“Because nothing hurts her,” said Saba.

“No, I’m just better than them, that’s all,” said Karina. She had never told anyone about the Little Friends. That was her secret, and instinctively she knew she’d better keep it. Felinos with real peculiarities — as distinct from Saba who was simply not strong — had a habit of being found dead.

The sailcar reached the downgrade and roared through Camelback Funnel with the speed of a galloping horse, and the girls shouted and laughed with excitement as the craft bucked from side to side and the guiderails screamed a warning. Teressa stood guard over the brake lever, daring Enri to approach, knowing that this strange True Human friend of theirs would never get involved in a physical struggle with them.

“Karina — just go and put that brake on, will you?” Enri pleaded, hanging onto a stanchion with his one hand.

But Karina was yelling with the fun of it, standing on the prow of the Estrella del Oeste like a beautiful figurehead, braced against the handrails. “No way!” she shouted back against the bedlam screeching of tortured wood. Enri sniffed, smelling hot bearings.

Then he thought: what the hell. Just for a few moments he’d forgotten his need to rearrange the world’s history.

Too soon they reached Rangua South Stage, the shanty-town of vampiro tents at the foot of the hill on which stood Rangua Town. Teressa surrendered the brake, laughing at him with slanting eyes as he hauled on the handle and managed to bring the runaway car to a halt. The girls climbed down, calling to the felinos and showing their legs. The felinos, mostly bachelors but with a few fathers among them, muttered disapprovingly at the association between the girls and a True Human.

“He’ll kiss you while he stabs you in the back, Teressa!” one of them shouted, repeating the traditional saying about True Humans, although in expurgated form out of deference to her age.

Then they hitched up the shrugleggers for the two-kilometer climb to the town. The running rail descended to ground level for this purpose; the gradient was too steep for any sailcar to climb unassisted in anything but gale-force winds. Ten shrugleggers sufficed for the job, and with oaths and yells from the felinos the Estrella del Oeste was soon moving again.

Enri slackened off the halliard and furled the sail. Now that the girls were gone and the exhilarating ride over, he felt let down. A surly felino sat on deck, another led the shrugleggers. The wheels creaked, the car felt heavy and dead. The felino on deck had his back to him, sitting on the prow where the lovely Karina had stood, his legs dangling and his head bowed, half asleep, his neck vulnerable to an ax blow.…

Now that would change history.

That would be just the kind of open clash between True Human and felino which was needed to spark off the present tinder-box of relations.

There was an ax hanging from the shrouds for use in an emergency. Enri took it down and hefted it in his hand. It was heavy but well-balanced, and the blade was the keenest flaked stone. Enri often did illogical, crazy things.…

But the felino would bleed, and maybe hurt.

Enri put the ax back and stared at the eastern sky which was brightening with dawn.

“Haaaar!” he cried. “Har! Har! Har!” And he slapped his hand against the mast, again and again.

The felino looked round; a quick askance look.

Then Enri heard a noise below, a clatter and thump against the squeaking and rumbling of Estrella. Somebody was down there. An intruder, in his private domain. Somebody fooling with his things, robbing him, most likely — maybe even a bandido.

He took up the ax again and, yelling, descended the ladder into the cabin.

“I’m going to kill you!” he shouted, staring around the dark interior. “I can see you.” But he couldn’t. He was shouting to cover his own nervousness. A felini, however — with those catlike eyes — could see him.

“You wouldn’t kill me, would you, Pegman?” said a soft voice.

He dropped the ax. “Where are you, Karina?”

“Sitting on your bed.”

“Why?” He forced his mind away from the mental image of warm limbs, a slim body dressed in alpaca, and said, “I don’t need to kill you. Your father will do it for me, when he finds out where you’ve been. Now — what do you want?”

The car moved out of the trees and a pale glimmer of early daylight came through the porthole. Karina was a dark silhouette. She said, “Tonight I met a queer woman. She said she was the handmaiden of a bruja called the Dedo. You’re a wise man, Enri. You know more about the world than I do — and you’re a True Human too. You know the legends, and you sing songs of the past. Why would that woman have said I would become famous? And she did heal my leg; she really did.”

The Dedo.…

The word struck a chord in Enri’s memory.

.… There was a dense jungle and the harsh screaming of birds, and he’d left the other trackmen and gone exploring.…

And a monster had charged him, bursting out of a thicket.

Huge it was, and terrible, carrying an aura of unspeakable evil. Not jaguar, nor bear nor cai-man, yet possessing the most fearful characteristics of all three, and bigger than any of them, bigger even than the mythical thylacosmilus, about which he’d sometimes sung songs. But he never sang songs of this monster, in the years which followed.

So he ran until he collapsed sobbing with fear and exhaustion beside a stream, and while he lay there a girl came to him — a girl beautiful beyond measure, more beautiful even than Corriente, his love; but cold.

In a voice without expression she had said, “Don’t be alarmed. Bantus will not harm you now. You are outside the valley, you see.…” And they had talked for a while, of Time and happentracks.

I am the Dedo, the beautiful girl had said. You will never forget me.

“What else did she say? Can you remember the exact words?”

Surprised at the tenseness in his voice, Karina said, “I didn’t understand a lot of it. She used strange words. The Greataway — that was her word for the sky, I think. Ifalong.… Other words. That’s it — she said, ‘In certain tracks of the Ifalong you will be famous.’ Me, famous? What do you make of that, Enri?”

“If the Dedo’s handmaid

en said you will be famous,” said Enri carefully, “then I think you will. I met the Dedo myself once, and I believe her.” He tried to smile. “People will write songs about you. Maybe I should write one, to be first.”

“But what are tracks of the Ifalong?”

“The Dedo says that Time consists of happentracks, all branching out from the present. So that at any moment your future might go one way or the other, depending on what you do. The Ifalong is the total of all these happentracks in the future, when there are a billion different ways things might have happened. One thing the Dedo can do, is to see all these happentracks in the Ifalong, and work out the course people ought to take.”

Karina caught a glimpse of immensity. “Ought to take, why? What’s the purpose? Why not just live?”

“I think she thinks there’s more to life than that. But she didn’t tell me what.”

Karina was thinking deeply. “I wonder.… Do you think it might be possible to change things, by jumping onto another happentrack which had branched off some time before? Suddenly find yourself in a different world, where.…” Her voice trailed away. She was going to say: where my mother is still alive.… “No,” she said. “You’d have to do something so strange that it was completely out of place in your happentrack, something which simply didn’t fit in with the way things are, something —”

“Yes, you would,” said the man who thought coolly of murder, and was given to meaningless bursts of shouting, and who perched on rails flapping like a bird.

On Urubu’s deck.

The southbound dawn sailcar was captained by the infamous Herrero so Karina hung about the station for a while, drawing curious glances from True Humans who wondered why she hadn’t returned to South Stage with the other felinos.

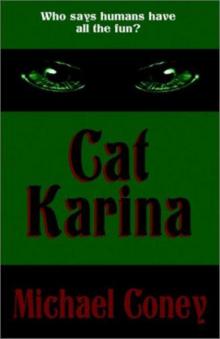

Cat Karina

Cat Karina